The cultural battles of sixties still occupy the imagination of Western elites. Some conservatives and feminists identify the sexual revolution as the root cause of developments that only unfolded decades later, and some mainstream voices argue its work must now be completed. Liberals routinely warn of conspiracies to drag things back to the fifties, as though that decade was nothing more than the shadow of the sixties. Martin Luther King and Malcolm X are routinely invoked to explain the state of race relations fifty years after they died. A film about Elvis ties his life to the Altamont Festival and Sharon Tate’s murder, as though the eruptions of ’68 mattered to his cultural relevance. Even the most bizarre fringes of futuristic philosophies explain themselves with platitudes by Dylan.

Our putative masters cannot leave the sixties behind them. Many of the people using the decade as a cultural lodestone weren’t even born when it died. Even their parents were children when its dramas played out. This cultural stasis is revealing. It tells us something about the elite: they cannot admit something that everyone else knew by the mid-seventies. Before getting to that, though, I want to dwell on how strange their obsession with the decade is.

I’m middle-aged now, but the sixties were never mine. They might give each new generation of our political class their stale cultural context, but I grew up in a more creative world. In Yorkshire in the eighties, the sixties did not provide the context by which we understood the world. Punk did.

The next few paragraphs will probably work better if you have audio and click the links.

Someone else who was there remembers:

Thatcher was in power

Times were tight and sour

The letter ‘A’ was sprayed in a circle everywhere

The circled ‘A’ was all over the place; but so was ‘NF’, the horizontals of the ‘F’ thrusting like straight-arm salutes from the last vertical of the ‘N’. If you were a teenager who cared about politics, then you were anarchist or fascist. No-one imagined Westminster would ever have our backs, and we didn’t change our minds when we grew up. When we were old enough to vote, we didn’t bother on an unprecedented scale. Later, politicians and journalists would worry that Brexit indicated dissatisfaction in the North. This illuminates only the depths of their ignorance. Discontent didn’t burst suddenly into middle-aged minds. It has been there since we were running down alleys with aerosols in our pockets.

But few of us even cared enough to deface walls. Better things were going on. We had a culture exploding with creativity, with an aesthetic of joy in desolation. What do I mean? I mean ‘this town is coming like a ghost town’. I mean ‘no future for you!’ I mean ‘I am a poseur and I don’t care’. I mean kids from Bradford singing:

The kids of the Coca-Cola nation

Are too doped up to realise

That time is running out

Nagasaki's crying out

I am calling this culture and aesthetic ‘punk’ as a shorthand. Punk music, though, was only a fragment of it all. White kids blasted Warrior Charge from bedroom windows, and reggae taught them the other side of the headlines. Dubplates and versions inspired them to ignore the corrupt old game of stars and labels. We listened as America’s desolate joy echoed our own. A tape burned through school like wildfire, quality degrading with every copy. On one side was It Takes a Nation of Millions and on the other was Straight Outta Compton. Both were cut short after forty-five minutes. It didn’t matter. The lyrics resonated with the force of truth. We knew our police liked racist violence too. Here’s a schoolyard song about them:

When all the lights are flashing

We’re going p***-bashing

The slur is ugly, and we knew it, and we didn’t care. It trapped weak teachers into defending the indefensible. Either they lied to our faces or they admitted the truth and buried our crime beneath those of the authorities. Our childish joy was more savage than rage.

We inherited a wasteland and we danced in it. We made the ruins sing.

Those days are as distant now as the sixties were to them. Financial bubbles turned the ruined warehouses where we danced into smart, empty flats, investments for speculators. The nightclubs are dying with their town centres. It’s a new time, and someone younger than me would have to write about growing up in it; but, when they do, the tales they tell will be even more distant from Sgt Pepper and Haight-Ashbury than mine are.

So why do those that would lead us treat the sixties as though they were our Heroic Age?

My theory is very simple: it was the last time that any of them mattered.

Those on the left pretend that society can be guided with the right policies from powerful institutional centres. They flatter themselves otherwise, but so do those on the right, even if their versions of ‘right policies’ often involves slimming down some institutional centres. The seventies taught us a harsher lesson. They ended one of modernity’s founding political myths, the idea that the vast bureaucratic engines the modern state uses to intimately order the lives of millions could be understood as a variation on the Greek city-states. They cannot: a modern state is a different order of being. It cannot be controlled by institutional centres, and even those centres can no longer be controlled. Any attempt to limit them only renders them more powerful. Nowadays, even the Machine’s smaller cogs are too big for human hands. This is the truth that our ‘leaders’ cannot even whisper. For if social institutions have become invulnerable to meaningful control, then their entire caste – politicians, journalists, civil service managers, researchers, and all – serve no purpose. To admit their pointlessness would end them. So, liberal and conservative alike, they retreat to the sixties and pretend that it matters as they launch into another round of culture war. It doesn’t matter and they don’t matter. They cannot prevent the end that is coming.

The rest of us may as well leave them in their imagined decade. In fact, we did. Another bunch of kids from Bradford sang about the Machine and its end years ago.

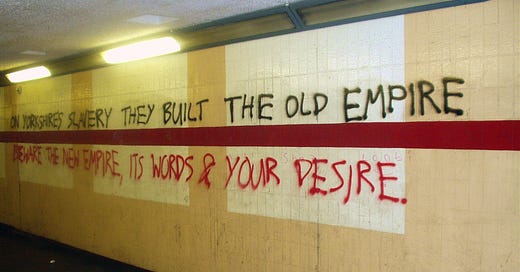

Image: On Yorkshire's Slavery They Built The Old Empire... by Tim Green. (CC BY 2.0).

I liken growing up gen-x as being born after a cultural neutron bomb had been dropped aka, "the sixties". All the structures of "the fifties" were intact but everything had died. The whole thing was a sham and a lie but few people would admit it. Maybe that's also the reason for the popularity of zombies since then.

This is good stuff, brother...

This is kind of how I have been feeling lately. I grew up right outside of a dying city in a "broken-collar" neighborhood. So that desire to build something different was baked into all of my friends. Unfortunately, the opioid epidemic ran right over many of them. It has been frustrating watching how things have been unfolding. I would say that we are obsessed with using outdated 20th century ideas to confront 21st century problems. Anyway I'm happy to stumbled across your writings. I look forward to reading more.