This post is a continuation of a conversation triggered by this article by Jack Leahy. I responded here, and he responded to my response here. Now, I respond again.

In Into the Far Wilderness of Sanity, Jack Leahy makes a strange argument, so strange that I cannot think of another example of it, even among fellow travellers such as Paul Kingsnorth or Plough. It is also, I think, important.

The article is not strange because it describes how modernity destroys its own promises and leaves us ‘stuck’. Illich did that well fifty years ago, and he was not the first. It is not even strange in saying that we need to ‘remove ourselves’ from the situation. Every generation creates intentional communities animated by that spirit. They mostly fail.

Saying that asceticism is the only way that we can ‘remove ourselves’ from this situation is a little stranger. Most writers, even ostensibly religious ones, flinch before writing something as direct as ‘anyone not willing to sacrifice and experience pain to achieve a goal will not get very far at all’. Instead, the usual thing to do after recognising we need to ‘remove ourselves’ is to gesture towards a social movement or leader – perhaps a new St Benedict – you would like to come along and fix things. Into the Far Wilderness is not like this. It is not waiting for the stars to align.

Stranger yet, this hard line does not rely on the Christian tradition that Jack is part of, or on any religious tradition at all. As I understand it, the basic argument is as follows:

1. Our society operates in counter-productive ways that are so detrimental to us that they inhibit our ability to live fully human lives.

2. The source of these counter-productive ways of being, or at least the reason they are omnipresent, is our own will-to-power.

3. Therefore these counter-productive ways of being cannot be addressed by ambitious social programs or normal politics. Such approaches nurture will-to-power and ‘the more we try to extend our will-to-power into the world of ambition the less human we are, and the more we atrophy’.

4. This atrophying of our humanity can only be addressed at the root, with an ascetic training regime that subdues the will-to-power itself. This is each individual’s first task, although ‘we can help each other’.

Notice how austere this argument is. A belief that our current way of living is inhumane can rely on little more than an awareness of how historically strange a life of overabundance and staring at screens is. Similarly, diagnosing the root source in humanity’s will-to-power is an anthropological observation before it is a spiritual one; and the solution of ascetic training requires little more motivation than the observation that humans learn by practice. The article’s strong line on the need for spiritual discipline is based on a naturalistic argument, one that an atheist could endorse. This is a little strange.

Yet even this isn’t the strangest thing about Into the Far Wilderness. The strangest thing is that it isn’t selling much. The fake ascetics I mentioned in my last essay usually offer two false hopes: hope for easy victory and hope for moral purity. The article, in contrast, prescribes a difficult regime of self-discipline for something it has already told us is ‘largely impossible’. It promises no victory, and offers little hint of a final escape from the Machine. The last, and most optimistic, section is called ‘Stepping on the Long Path to the Desert beneath our Feet’, which is pretty much the opposite of advertising. Similarly, it promises no purity. It calls its own asceticism ‘hypocritical’ because it is for people still caught in the webs of globalised consumerism. Instead of promising you will be unsullied by the world, it promises nothing but hard work for an uncertain reward.

So the essay is strange, but it is also important. Obviously, if it is right in its diagnosis of human atrophy caused by will-to-power and its prescription of asceticism, then this is important to each of us individually. I am more interested here, though, in its political implications. By ‘political’, as always, I mean this in Aristotle’s sense of communal orientation towards the good life and not in the contemporary sense of empty mediated chatter.

First, though, I feel I should defend Jack from a charge he has brought against himself: hypocrisy. Not because hypocrisy is such a terrible thing. As Judith Shklar observed, the world contains many unavoidable choices between evils, so each society must decide which vices it finds worse than others. A hypocrite is easier to mock, but a cruel person is guilty of a far worse evil. I do not, however, think that Into the Far Wilderness is even hypocritical. To fail to reach lofty goals is not hypocritical, and even to publicly defend those goals while knowing you have failed to reach them is not hypocritical if you are open about your limits. I do not think that the self-directed charge is made out.

Nevertheless, ‘hypocrisy’ is close to something important about this strange asceticism, the way it tells you that the goal is almost impossible but that you should strive for it anyway. That deserves a name, but I think ‘ironic asceticism’ is a better one than ‘hypocritical asceticism’. Let me try to explain. One of Kierkegaard’s pseudonyms described mistaking irony for a mere ‘figure of speech’ as ridiculous, and I do not want the reader to think I have fallen into that error. I mean irony in the sense that Jonathan Lear, in his book inspired by Kierkegaard, called ‘a form of existence’. This mode is best captured by an ironic question: in this context, ‘among all ascetics, is there an ascetic?’

The question is ironic, not circular. The left ‘ascetics’ names all who practice asceticism, all their practice, all their attempts to improve their practice, all their reflections on it, and even the way that the ideal of asceticism guides their practice. The right ‘ascetic’ names only the ideal itself, which animates everything in the left term and yet is somehow always beyond its grasp. The experience of irony is the experience of living the left hand term, committed to the right hand ideal and yet, comically, always falling short. It is the experience of a man who spends hours crafting serious articles about asceticism on his laptop when he could be meditating. It is the experience of the believer who in the midst of devoted prayer wonders how mere prayer could ever be enough. Notice how different these examples are to the hypocrite who, not being truly committed to the ideal, experiences no internal contradictions. The ironist, because they are committed absolutely, must fail absolutely; yet it is only the completeness of their failure that reveals the transcendent nature of their goal. If stepping outside the Machine were possible, then it would not be necessary.

Irony is politically important. It is important because anything less than an unreachable ideal will be caught by the Machine, eviscerated, repackaged, and sold back to you in a form that is exactly the same apart from the way that it drains everything good from your soul. No idea, no belief, no institution, and no practice is beyond the Machine’s grasp. Only the ideal, being formless, is safe. Of course, the ideal, being formless, is also beyond our grasp, so we cannot cling to it for safety. If we try, then we will cling instead to our idea of it; and if we do that, we will soon find out that our idea was the Machine’s all along. The only way to succeed is by committing so completely that failure is inevitable. And this is the other reason why we need irony. The completeness of our failures reveals to us the depths of our absurdity. This is a gift. Will-to-power needs us take ourselves seriously. It is the product of pride and it struggles when we genuinely laugh at ourselves.

Lear writes about the ironical mode as a human excellence that can be learned. For Jack, asceticism is the same kind of thing. They are both ways of being that become accessible through the discipline of training. They are, as an Aristotelean would put it, virtues: habits that orientate us towards the good life. For creatures such as us, the good life is always social, always political in the broad sense; and I think this detail is key to understanding the importance of asceticism and Jack’s strange argument for it.

He writes about the benefits of ascetic practice for the ascetic. I am sure that he is right about them; but politically, and perhaps spiritually, these benefits are beside the point. The purpose of virtue is not to benefit the virtuous person. As Peter Geach wrote, ‘men need virtues as bees need stings’. The sting benefits the hive, not the stinging bee, who dies. So, I suspect, it is with asceticism. Even if the long path to the desert does not benefit the walker at all, their path still has purpose. It is the rest of us, sleepily staring at screens in fading luxury, they will benefit. The desert is slowly coming to us all, and we will need people who know how to live in its stark beauty.

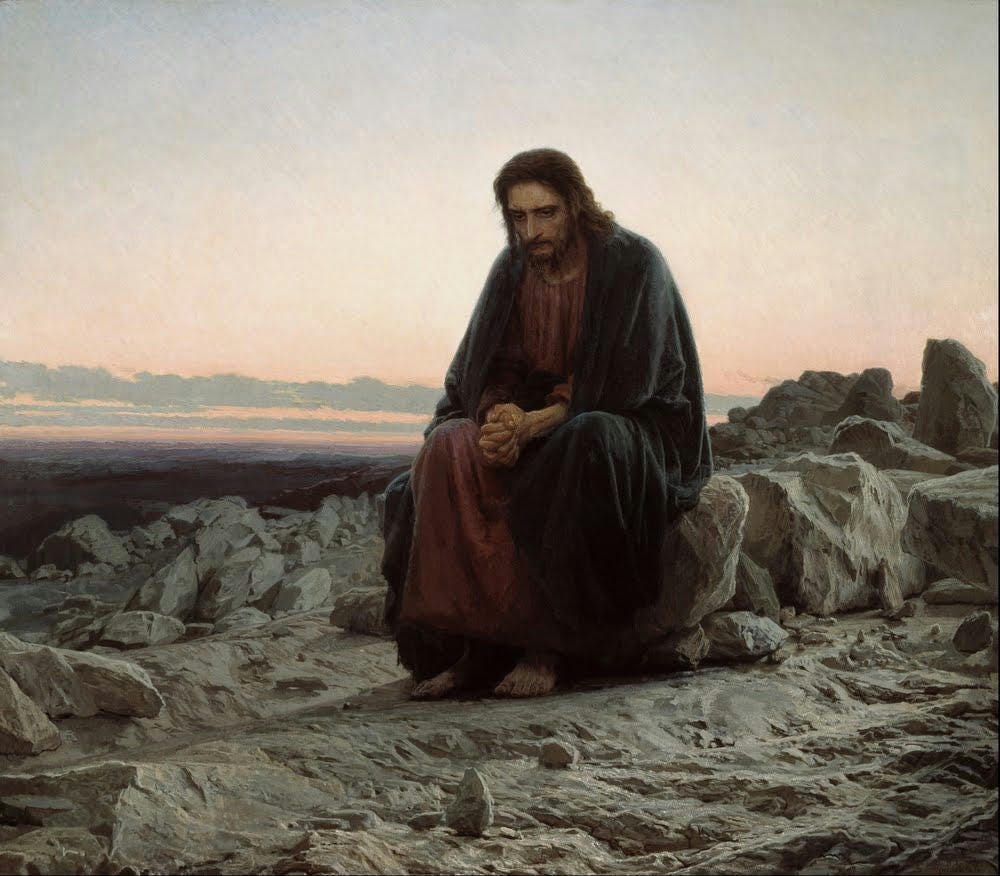

Image: Christ in the Wilderness by Ivan Kramskoi. With thanks to Richard Morris for mentioning it.

The machine does a real good job of absorbing and regurgitating counter culture. The best examples, at least in my experience, are from American television. The first was the neutralizing of the Beats, that was finished when Bob Denver, as Maynard G. Krebs, walked into American living rooms in the sitcom Dobie Gillis.

The hippies were subsumed once the major department stores started selling tie-dyed clothing, and Hip-Hop got theirs when Snap, Krackle and Pop hip-hopped their Rice Krispies box across the breakfast table.

It does take that willingness to give all and fail for a path that the machine can not co-opt.

I need to give this essay some more thought. The machine runs to fast at this moment

But I’d gently push back at the assertion that Jack’s prescription lies outside of the Christian tradition. I think it’s its (:) ) deeply buried heart. So deeply buried that the well needs folks to drag the wretched blocking boulders away with their bare hands. Jack’s encouraging this in his take on asceticism. The deep well is Paul’s‘when I am weak, then I am strong’ ‘the Powers come to and End in weakness’ Those who die (to will to power) Live. Kenosis

A river flows or it isn’t a river

But in flowing it’s doing nothing and achieving everything

Ramble

Ramble

Thanks FFlatcaps

God Bless the White Rose