Disquiet

On ghosts of nature

There’s a mountain, but not a Himalayan one. Don’t picture crisp edges and permanent snow. It’s an English mountain: old and round, green-skirted, rain-wreathed. It might be in the Lake District. Clouds water it; and the droplets, landing, unite in trickles and streams. They river at the mountain’s foot.

The mountain, clouds, and river are invisible to me. I only see rain running downhill.

Ghosts haunt the flat present, ghosts of nature. They haunt an elite environmentalism that frowns at a wood-burner but smiles at an airport expansion. They haunt a culture that can read worries about collapse only as consumptive fashion’s newest trend. They haunt me when I reach for a metaphor and the old man passes me a mountain.

In cliché, a ghost is a ‘presence’; but it’s not. A ghost is a felt absence. We are haunted by the absence of nature.

What does that mean? What could it even mean for nature to be absent?

There’s a sense of ‘nature’ that does not haunt, nature as the firm edge of possibility. It’s unnatural for a human to fly unaided, so it never happens. This form of nature is not absent. It’s inescapable. Not even the wildest fringes of the reigning machine-cult oppose it. Because nature in this sense is implacable, they oppose their own humanity instead. What is this nature? I don’t know. Call it ‘The Mountain’.

Another sense of ‘nature’ gets its form from the first. With a plane, flying is not impossible, yet it is unnatural. For most of our history, we didn’t fly at all. Suddenly, many sometimes do. It’s the same with other wonders, from travelling at fifty miles an hour to addressing an audience scattered across the globe. These things break with what came before and leave us haunted by what we were. Heavy clouds release a downpour onto the mountain. The waters overspill their channels and wash over the gaps between. So it is with us. The flood of humanity has carried us into unshaped spaces, but we have not entirely forgotten the old stream beds. Call this ghost ‘Remembering Before’.

不 可长保 – this cannot be long sustained.

As the first sense of ‘nature’ gave us a second, so the second gives us a third. Before, we lived in a world that we didn’t make. We were just one species among many. But we made the cities and bent the fields and hills into lies. When a mountaintop inconveniences us, we remove it. We’re haunted by the silence of the non-human. The downpour intensifies. The floodwaters scour the mountainside, uprooting trees and stripping earth from rock. The wave of humanity washes away everything, but we have not entirely forgotten seeping through soil instead of washing it ahead of us. Call this ghost ‘Being Alone’.

Remembering Before and Being Alone are silent ghosts. They don’t judge. Species change, what they are now is never what they were before; so Remembering Before is wistful, but not angry. Species shape their world, the Earth doesn’t shudder when one dominates awhile; so Being Alone mourns, but doesn’t fear the future. These ghosts don’t whisper. They don’t tell us what we should be.

There is whispering ghost, though, one that judges. It tells us we are not what should be. We hear its words, but they’re hard to understand. We barely fathom them; but, like listening to an argument in a foreign tongue, we grasp their tone. A gnawing sense that something isn’t right haunts the modern imaginary. It bubbles up in the mutable panics of left and right. It feeds the engine of eternal consumption. Cultures jolt and quiver epileptically to half-heard murmurs. Call the ghost that mutters them ‘Disquiet’.

It’s easy to name this ghost, but hard to describe it. A ghost is a felt absence, and Disquiet marks our lack of coherent moral language. Even to talk of it is to risk falling into its void.

Our lack of coherent moral language is also a ghost of nature, but this isn’t obvious. It takes a mind like a millstone to see it, a mind so heavy that no grain of experience escapes unprocessed. I don’t have that sort of mind, but I’m lucky. GEM Anscombe did, and has done my grinding for me.

If you look close, there seems to be a circularity in moral language. It’s most obvious with promises. I promise you a wheel of cheese when it matures; so when the Wensleydale is ready, I have to give you one. Why? For no other reason than I promised it. The duty seems self-referential.

It does no good to try to sneak around this circularity by talking about how you expect cheese now that I’ve promised it or how society runs better if people keep their promises. Such explanations move the goalposts. Instead of answering ‘why must I keep my promise?’, they instead answer ‘why should a society have the practice of promising?’. The second question is a good one, but it’s too fast. To see what used to be in the gap that Disquiet marks, we must grind much more slowly.

Given that the practice of promising exists, the reason that I must fulfil my promise to give you cheese is no more or less than the fact that I promised you cheese. Your expectations are irrelevant. Maybe a lifetime of betrayal has left you suspicious. Do I therefore owe you the cheese less than if a comfortable life had made you a trusting type? No. I owe you cheese because I promised it. The proper ordering of society is similarly irrelevant. If rules-utilitarians armed with computer models determined that society runs best without promises, would I therefore no longer owe you the cheese? No. If foolish enough to believe rationalists and their machines, I should stop making promises; but I have already made this one, so I still owe you cheese. The power of the promise belongs to the practice of promising.

Promises are a good starting point because their seeming self-referentiality is obvious, but rights and rules are little different. Imagine you are in one of those chain coffee shops with baristas who write your name on a paper cup. You pay too much money for a liquid cake that kicks like amphetamine, and shuffle off to the side. As you wait, someone else’s cup is put out, ready to collect. ‘Huizi’ is written across it. You’re not Huizi. You look around. You seem to be only customer here. Impatient for coffee, you reach for the cup. The barista looks up and says ‘You can’t take that’. What does she mean?

The barista is not talking about physical impossibility. She’s stuck behind the counter and there’s no sign of anyone else. Physically, you can pick up the cup. Nor is she talking about consequences. Perhaps you’re an athletic stranger to the city, confident that you will not get caught and punished. She is, however, making a moral claim. If asked to explain, she might say something like ‘It’s Huizi’s coffee’. The apparent circularity of moral language reappears. To say the coffee belongs to Huizi is to say nothing more than that it is for Huizi to use and not for others, which is just the same thing as saying ‘You can’t take that’. The justification for his ownership lies simply in the practice of ownership.

If you were a fast-talking swindler, you could talk about how resources such as designer coffee should be handed out on a first-come first-served basis; but, as with promises, that would be changing the subject from ‘Why must I respect Huizi’s property?’ to ‘Why should a society have the practice of property?’. The second question is good; but if you proceed there too fast, you will leave a gap in your wake, one called Disquiet.

As it goes with coffee cups, so it goes when the stakes are higher: ‘Why should I not steal this car?’ - ‘It’s Huizi’s’; ‘Why should I not kill this man?’ - ‘He has a right to life’; ‘Why should we not invade?’ - ‘They’re a sovereign people’. In each case, the answers – property, rights, sovereignty – simply restate the original prohibition. The power of morality belongs to the practice of morality.

To those familiar with Anscombe, there’s a puzzle here. Within the limits of my understanding, this view is hers. Yet to say that rules, rights, and morality are grounded only in existing practices sounds like relativism or social constructionism; and Anscombe was a devout Catholic and vigorous moral campaigner. What’s going on?

I have, of course, carefully said that moral language seems circular, not that it is circular. For millennia, water washes down the mountain, imperceptibly wearing grooves and slowly making streams. Why does the water fall this way? Because of the shape of the mountain. Why is the mountain shaped this way? Because water fell this way. This is not an example of circular reasoning. It’s a description of a long mutualistic relationship. So it is with morality. Why do people make promises? Because societies are structured so they do. Why are societies so structured? Because people make promises. There’s only a circle here if history is forgotten and it’s imagined that mankind has transcended time. That’s always a mistake. History has weight. If morality truly were circular, then the relativists and constructionists would be right; but it’s not and they’re not. Morality is shaped by long practices, ones that precede writing by aeons. Humans living now could no more end the practice of promising than a spring shower could wash away the Ouse.

This reveals the shape of Disquiet. When moral claims are made without the grooves of long practice they feel hollow, brittle. When morality becomes detached from tradition, it’s no longer self-sustaining. A need for ‘foundations’ is felt; and, thrashing around, philosophers find things they think will do: ineffective appeals to God’s command, the alleged dictates of universal rationality, the deceptive mathematical simplicity of utility. None satisfy. Each justification aspires to the form of a rational claim. They fail to hit even that target, but the shoddy workmanship of great minds is besides the point here. Words never could offer the justification morality requires. It needs a groove worn deep by practice, and theory doesn’t scratch the rock. As humanity spills out of its channels, a ghost is born: Disquiet.

Beneath the floodwaters, old stream beds remain. Long practices continue. People make and honour promises. A barista looks up and says “You can’t take that”. Mankind has not fallen into some complete amorality. Disquiet does not mark old ways being lost forever. It marks the feeling a single drop of rain has landing in the great downpour. Sometimes, almost accidentally, it follows the path of an old stream. Sometimes instead, it forms part of a great sheet of water that falls over the spaces between. It’s hard for the droplet to tell the difference. All the old shapes are submerged. In the same way, we wash across the long practices, but find it hard to know where they are. Disquiet marks our lack of knowledge.

If Disquiet is the ghost of old practices, then why do I say it’s the third ghost of nature and not just a ghost of history? It’s both. Before the flood, before Being Alone, humanity only slightly shaped its own ways. The long practices were shaped by the world and other creatures. Only a fool would believe our long association with wolves and dogs has left us behaviourally unchanged, but it’s still a new episode in the history of our species. Just as societies and moralities grew together in long mutualistic relations, so both grew in long mutualistic relations with the non-human world.

‘Natural’ in this sense is not mysterious, but nor is it narrowly deterministic. It’s natural for humans to be born with ten digits, but sometimes people are born with more or less. Similarly, it’s natural for parents to nurture their child, but some do not. Again, it’s natural to give even portions for equal work, but not everyone does. The first of these is a deep stream in the physical nature of mankind, the second a deep stream in the behavioural nature of mankind, and the third a shallower behavioural stream; but ‘natural’ has the same sense in all three.

This view is not a thousand miles from Philippa Foot's. Moderns would call it a virtue theory; but we must slow down again. Shallow thinking about virtue can give a reassuring sense of certainty to the chaos of life. Some who make the connection between nature and virtue think they have found fixed constellations by which they can navigate. They haven’t. All certainty is illusory. The stars move.

The structure of virtue is purely formal. A virtue is a relationship between moving parts, not a solid rock to which you can cling. Zhuangzi saw it:

‘One of Robber Chih's followers once asked Chih, "Does the thief too have a Way?" Chih replied, "How could he get anywhere if he didn't have a Way? Making shrewd guesses as to how much booty is stashed away in the room is sageliness; being the first one in is bravery; being the last one out is righteousness; knowing whether the job can be pulled off or not is wisdom; dividing up the loot fairly is benevolence. No one in the world ever succeeded in becoming a great thief if he didn't have all five!’

Although this passage mocks the Confucians, Zhuangzi is as serious as he is playful. A sagely, brave, righteous, wise, benevolent thief doesn’t thereby become a saint. He becomes a great thief who can cause greater mischief than the usual type. The greatest virtues are the soil that nurtures unparalleled vice. What, then, should be done? Zhuangzi says:

‘Cut off sageliness, cast away wisdom, and then the great thieves will cease. Break the jades, crush the pearls, and petty thieves will no longer rise up. Burn the tallies, shatter the seals, and the people will be simple and guileless. Hack up the bushels, snap the balances in two, and the people will no longer wrangle. Destroy and wipe out the laws that the sage has made for the world, and at last you will find you can reason with the people.’

Just as moving too fast makes Anscombe look like a relativist, so moving too fast makes Zhuangzi look like a nihilist. He’s not. Although he calls for virtues to be ‘cast away’, it’s to end the reign of the great thieves. Although he calls for the laws to be destroyed, it’s so you can ‘reason with the people’. There’s something he’s moving towards.

There’s a wood in the valley where I sometimes walk. Hours after a downpour, you can still hear the rain dropping from trees to ground. Be that slow.

The traditional solution to the problem with Robber Chih is to locate a fixed point somewhere else. Then you say that the virtues are only really virtues when they guide you to the fixed point. For the Platonist, the fixed point is the the form of the good; for the Aristotelian, it’s eudaimonia, flourishing. All such solutions fail. Ensuring the flourishing of his band of thieves, Robber Chih became a threat to all around. Seeking his compatriot’s good, he terrorised his neighbours. When Chih’s atrocities became infamous enough, an even greater thief, one so vicious the whole world called him King, killed the band and stole their treasures.

Some reach this point and sink into a defeated kind of utilitarianism. They say Robber Chih went wrong because he didn’t seek the flourishing of all, or that he didn’t look to the greatest good. Seeing where their fixed point led Chih, they try to move it. But if you can move a point to keep your story straight, then it’s not fixed enough to navigate by. This reasoning is just a lie told by technocratic coercion, the urge to subsume all particularity to some higher abstraction. By this point, that Machine is exhausted and out of tune. It’s merely creaking ‘bigger is better, bigger is better...’ again and again. That’s all it ever did say, and it always was wrong. Sometimes the small must prevail.

A utilitarian lifeguard was walking along the beach. He looked to his left. A great white shark was attacking three women in a rubber dinghy. He looked to his right. A small child was drowning. Being fast at mental calculus, he noted that the women could easily make more children, so saving the three of them would undoubtedly lead to more long-term utility than saving the child. Being aware of virtue ethics, he also reasoned that if he promoted the flourishing of these three, they could, in turn, promote the flourishing of many others. He doubted any child who leapt into the ocean when they couldn’t swim was ever going to be much good at promoting flourishing anyway. Happy that divergent approaches to ethics led to the same conclusion, he leapt into the water and punched the shark on the nose, saving the women. Once the dinghy was dragged ashore, the first woman slapped him, the second called him a coward, and the third called him an idiot. No-one ever talked to him again.

Many of those who still talk of virtue – political perfectionists, integrationists, those that mutter about strong men making good times – are no better than the utilitarian lifeguard. They stand around the silly dying Machine and wonder how they could make a better one next time. They think virtue is virtuous because of where it leads; so they fantasise about remaking the world. They’re haunted. They talk of the classical age as though it was not a mere half-minute ago in the day of humanity, and Remembering Before smiles; for we were already haunted then. They assume that humans will shape what comes next, and Being Alone grins; for our power was only ever a playful loan from Heaven and Earth. They think they know where virtue leads, and Disquiet laughs; for virtue never cares where it goes. Virtue is pointless.

Water running downhill does not dream of the river. It’s just in its nature to fall. So it is with horses:

Horses’ hoofs are made for treading frost and snow, their coats for keeping out wind and cold. To munch grass, drink from the stream, lift up their feet and gallop this is the true nature of horses.

So, too, it is with us.

Lao Dan was walking along the beach. He looked to his left. A great white shark was attacking three women in a rubber dinghy. He looked to his right. A small child was drowning. He breathed in. One of the women punched the shark. He breathed out. The child’s father dived into the ocean. Lao walked on, enjoying the warmth of the sun and the cool of the breeze.

Image: Misty Mountain by Robin Mulligan (CC BY 2.0)

very interesting essay, I had to read it twice, slowly. I would like to be slow like the raindrops in your forest, but ‘I would like’ is too hasty. Did you study Chinese? I like the imagery of modern humanity as a flood spilling out of its channels; I especially like the three ghosts. I think that now, I can never rid myself of Remembering Before, Being Alone and Disquiet; they will sit there quietly, when I muse about life.

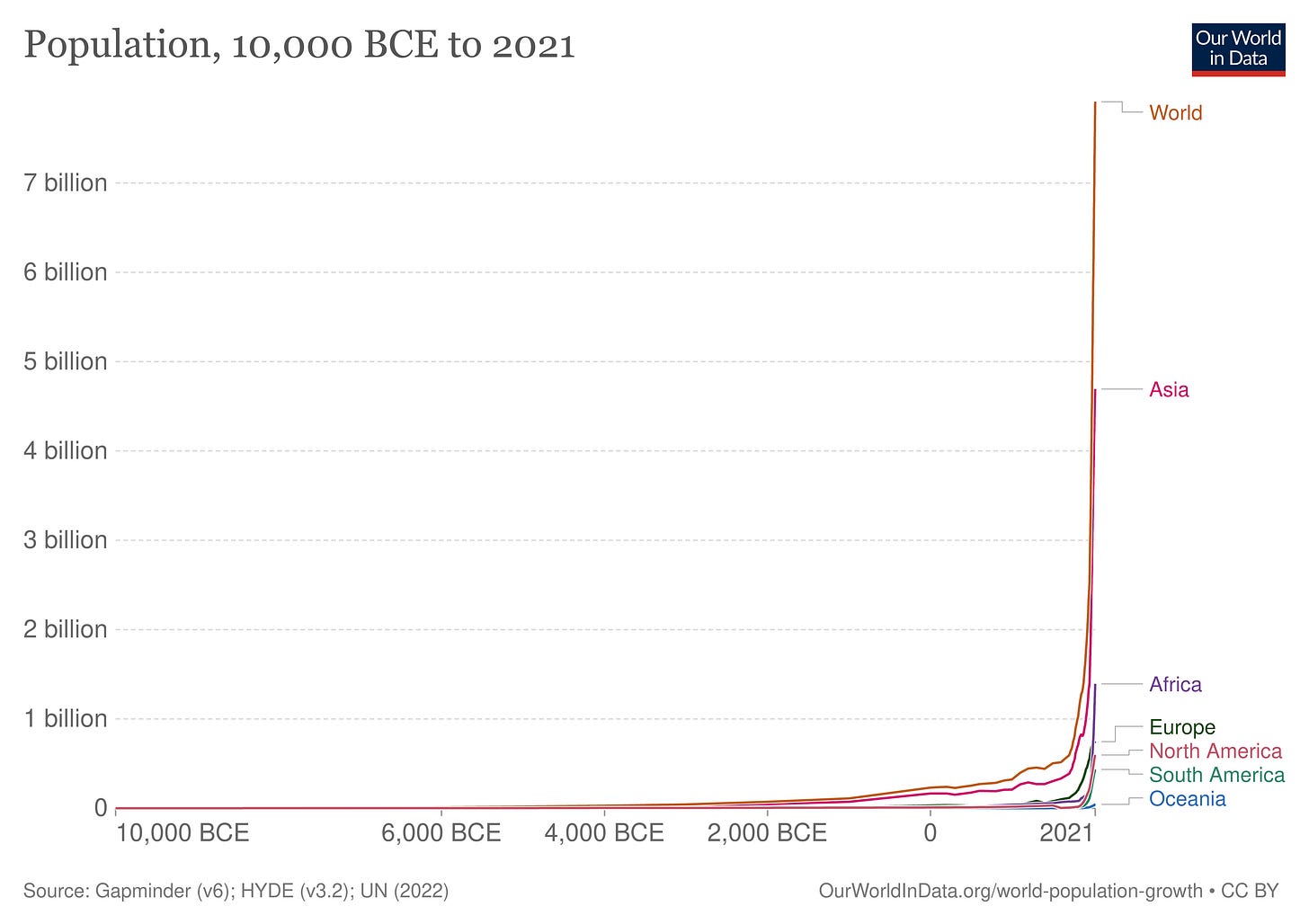

The graph you included in the piece says almost all that needs saying. I read the other day that 'the wild land mammals alive today have a combined biomass of 22 million tons; marine mammals account for another 40 million tons. By contrast, humans weigh in at 390 million tons - and if you throw in our livestock and our pets, that adds another 690 million.' We outnumber and overwhelm the world, and it is our loss.